This op ed appeared in the Houston Chronicle on February 24, 2021.

Opinion: Reliable water is a right, Houston don’t miss chance to make repairs for poorest

Opinion: Reliable water is a right, Houston don’t miss chance to make repairs for poorest

By Kristen Schlemmer

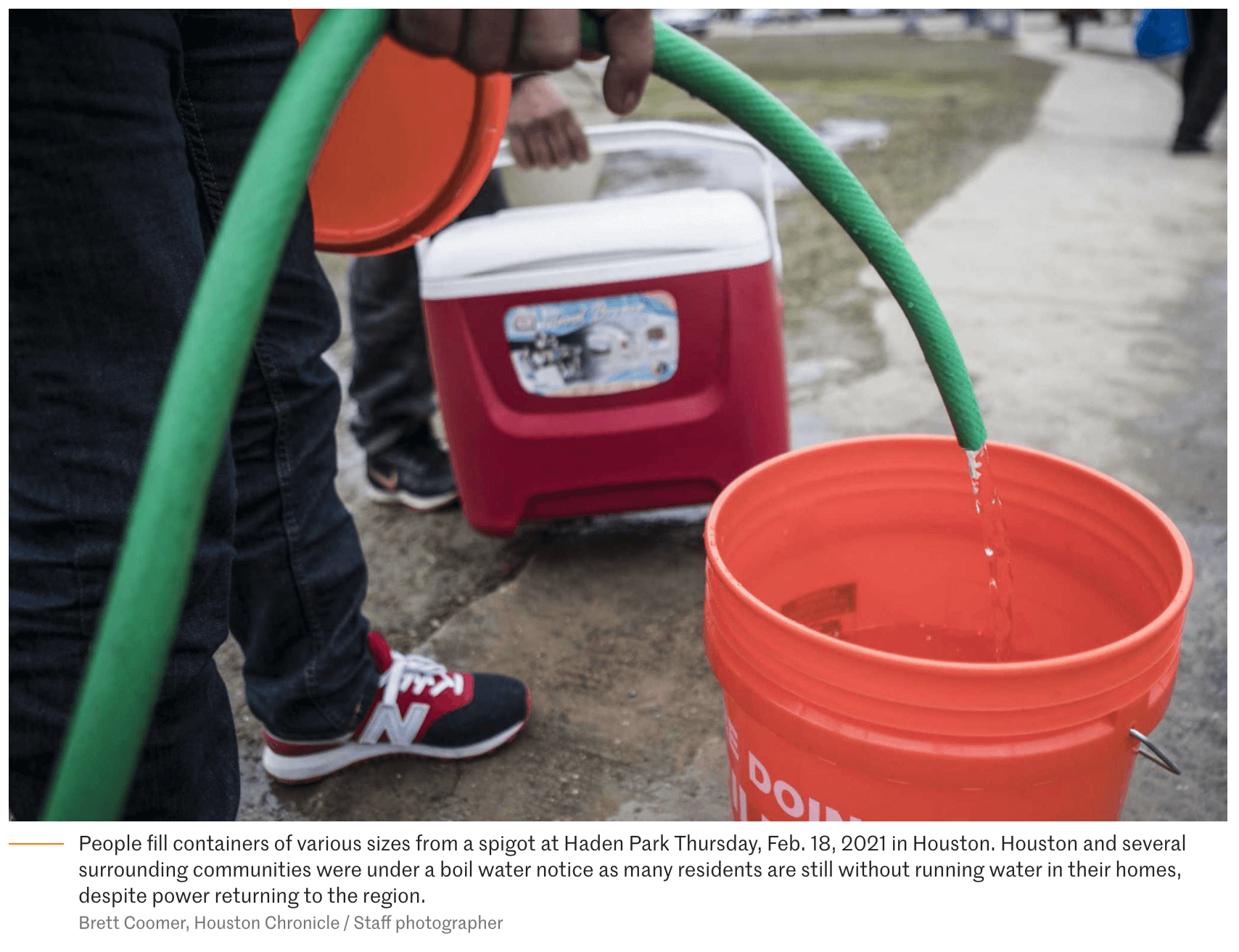

One lesson must not be lost as we move forward from this week’s intensely hard freeze: Infrastructure matters. When our water isn’t clean, or doesn’t flow at all, it wreaks havoc on every aspect of our lives. Over the last week, we went without showers, could not easily flush toilets and stood in long lines to replace dwindling drinking water supplies. For some, the pursuit of usable water became a full-time job.

As boil water notices are lifted, and we work to repair cracked pipes, for most of us, life will begin to return to normal (pandemic normal). But for many Houstonians, unreliable water and wastewater infrastructure is a way of life. Some of our neighbors across the city deal with toilet problems and dirty water on a regular basis — not just during intense storms. Sewage backs up into people’s homes and settles in the yards where children play. It creates a major health risk that no one should have to live with.

Houston is in a position to help these residents — but for years, it has taken the position that it won’t, simply because it doesn’t have to.

For over a decade, Houston has kept tabs on sewage backing up into our neighbors’ homes as part of its required reporting to regulators. These reports reflect the overall ailing state of the city’s wastewater system and document thousands more spills and millions of gallons of untreated sewage that have entered bayous where people canoe and fish and parks where kids play and people exercise all across the city for the last decade.

Only when threatened with a lawsuit under the Clean Water Act, the city claimed a fix, in the form of a legal settlement with regulators, was imminent. The city publicly promised the solution would include a project to replace defective sewer connections in a low-income area of the city most affected by sewage backups into their homes.

When the mayor and City Council voted to approve that settlement in the summer of 2019, they agreed to pay $4.4 million in fines and invest $2 billion in long-overdue infrastructure updates. But not a cent of this historic expenditure went toward the promised pipe-repair project to repair or replace the lines connecting homes and businesses to the city’s infrastructure. Instead, the settlement approved by the city left low-income residents to figure out their sewage problems on their own — or potentially face enforcement action. Although the city never explained why, the Trump administration’s whittling down of the use of a policy that made community-centered environmental projects a part of settlements possibly stood in their way.

As of this month, however, the new White House administration emphasized its support for community-centered projects and its commitment to undoing historical environmental harms to low-income communities, clearing the way for the city to deliver on its promise.

This means the city can help residents with sewer problems by working with the Department of Justice to redirect a portion of its $4.4 million penalty toward the pipe-repair project promised more than three years ago. Nothing in the legal settlement prevents the city and the new administration from working together to make this change. Reinstating this project now would also resolve one of the major objections raised by Bayou City Waterkeeper to the current settlement, clearing at least one obstacle to its approval by a local judge.

The time for the city to act is now. Once the settlement is approved, it will govern the city’s actions to fix its sewer system for the next 15 years. The city has a choice to make: Will it rest on a settlement negotiated with an administration that spent four years eliminating water protections and increasing threats to public health? Or, as residents across the city work to repair their pipes and increasingly look to the city for help, will the city prioritize clean, reliable water for all and deliver the program it promised nearly three years ago? The choice should be obvious.

Schlemmer is the legal director for Bayou City Waterkeeper, which uses law and science to push back against polluters and irresponsible developers, fill gaps in regulatory enforcement, and build local community power.