Introduction

At Bayou City Waterkeeper, we view water as a catalyst for change. In recent years, our growing team has developed a grounding in an intersectional, justice-oriented, bold stance on environmental policy that has made BCWK a vital part of protecting Houston’s waterways and communities. We have done this by centering our core values: interconnectivity, fluidity, bold action, justice and equity, and regeneration. This policy agenda reflects these core values.

Using science and legal advocacy, Bayou City Waterkeeper (BCWK) works with communities affected by water pollution and flooding across greater Houston to restore our natural systems, achieve equitable policy solutions, and advance systemic change to benefit all who live within the Lower Galveston Bay watershed. We hold polluters accountable and protect the water that flows through our bayous, creeks, wetlands, and neighborhoods into our coastal bays. We recognize the complexities of our watershed posed by historic disinvestment in infrastructure, loss of wetlands, industrial risks, and climate change. We aim to navigate the harms of irresponsible development and industrial activities by focusing on protecting the water, and being accountable to the communities we serve.

As we grow our work, and deepen our relationship with local and regional communities, we need to be rigorous about policy that ensures the lives and health of every community member in the Houston region who comes into contact with water. We need plans and contingencies to ensure the health of communities and ecosystems in Houston. This policy agenda is a research-based response, informed by the lived experience of community members, to these urgent needs.

Methodology

To create a policy agenda that accounts for both the communities that we serve and current political and movement synergies, BCWK developed – in partnership with the Center for Advancing Innovative Policy (CAIP) – a participatory agenda-setting process that centers the voices of a broad range of our partners and community leaders.

CAIP’s approach to developing a grassroots-anchored policy agenda for BCWK comprised three main steps:

1) an initial assessment, including a policy landscape analysis,

2) a comprehensive stakeholder process, and

3) synthesis, which allowed us to integrate ideas and prioritize our policy goals.

At the heart of this vision are the issues and needs identified by the BCWK team and our stakeholders. Over the course of several months, the CAIP team gathered data from several BCWK’s stakeholders, including movement partners, researchers, community leaders, and co-conspirators, as well as BCWK staff working directly with frontline communities. Once research and stakeholder data were collected, BCWK narrowed and prioritized this information, all while contextualizing current political realities, staff capacity, and stakeholder relationships. This research also places this policy agenda within the broader nexus of the movements for climate and racial justice in which BCWK already moves, as well as those with whom we are looking to build bridges.

This policy agenda is a result of those conversations and analyses. This set of policy priorities are deeply rooted in our values, our partnerships, and the communities to which we are accountable. Our goal is to remain grounded in political realities while pushing ourselves and our movements forward, blending the art of the possible with a broad vision for change.

DEMANDS

CLEAN WATER: A PUBLIC RESOURCE FOR PUBLIC HEALTH

Infrastructure Equity

Public utilities play a critical role in protecting the health of our communities and ecosystems through the management of water quality and infrastructure in their water systems, including wastewater, stormwater, and drinking water. In Houston, nearly 60 percent of the city’s 2,500 miles of waterways are contaminated and unsafe for human consumption or exposure, failing to meet the Clean Water Act’s goal of drinkable, swimmable, and fishable waters. A large source of pollution has been from failing sanitary sewer infrastructure and unchecked stormwater runoff. Historic disinvestment has left lower-wealth, Black and brown communities bearing the brunt of infrastructure failures. Clean water and effective waterways are not merely vital public facilities, but a requirement for our collective health and safety.

A sanitary sewer overflow (“SSO”) occurs when untreated or partially treated sewage is discharged from a wastewater collection system before it reaches the treatment facility. Sanitary sewer overflows are potentially harmful untreated discharges into local bayous, parks, and neighborhoods. These overflows have increased our vulnerability to illness and dirtied local bodies of water, and disproportionately impact low-income communities of color in our region. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, our state’s chief environmental regulator, has classified nearly half of our state’s bayous, rivers, and smaller streams as “impaired”—meaning that they are polluted and need to be cleaned up.

From 2011 to 2017, wastewater treatment facilities across our region reported over 13,000 overflows, representing more than 80 million gallons of untreated sewage, disproportionately affecting lower-wealth and Black and brown communities. A federal consent decree required Houston to invest $2 billion in sanitary and sewer upgrades over 15 years, but it left out funding for private sewer laterals, resulting in an unjust burden on people of color. This landmark settlement resulted from a federal enforcement action prompted by Bayou City Waterkeeper’s investigation in 2018. Similar sanitary sewer issues were identified in Baytown, leading to a federal lawsuit against the city for Clean Water Act violations.

The City of Houston and Harris County must close infrastructure gaps that disproportionately affect Black and Brown communities by investing in comprehensive water infrastructure improvements

- Create a $20-million Private Sewer Lateral (PSL) Fund to extend the benefits of Houston’s 2021 wastewater consent decree to lower-wealth Black and Brown communities.

- Implement the 2021 consent decree to serve communities experiencing the heaviest burden of sewage:

- In ongoing planning and implementation of the consent decree, make sure projects are closing sewage gap for homeowners who are at or below 100% of the state’s Average Median Household Income (AMHI) level

- Include a Supplemental Environmental Project (SEP) provision to redirect penalties from ongoing sewage overflows

- Establish a stipulated penalty provision to create a fund for sewer line repairs on private property

- Ensure equitable eligibility requirements and distribution of resources:

- Develop a data-driven approach to identify communities most in need of infrastructure improvements

- Implement transparency measures to track and report on the allocation of funds and project progress

- Implement a comprehensive assessment framework integrating socioeconomic factors, environmental justice metrics, infrastructure conditions, historical investment patterns, and water-related health outcomes to guide equitable water policy decisions

- Address sewage hotspots across our region where investment has long fallen short:

- In local municipalities, adopt consent decrees that address sewage problems in low-income communities through equitable investment, supplemental environmental projects, and stipulated penalty provisions

- Ensure that proposed wastewater plant consolidation does not result in a disproportionate amount of wastewater plants in communities of color, immigrant communities or low-income communities

Access to Clean and affordable drinking water

For the last two decades, the Clean Water Act has been a driver in our work to ensure environmental protection of our waters and communities. Within our watershed and region, there exists a critical gap in drinking water advocacy, a major public health and economic justice issue. Access to clean, affordable drinking water is a fundamental right that disproportionately affects low-income communities and communities of color, often burdening them with higher costs and lower quality water. Recent policy wins — such as the release of a new EPA rule to hold major polluters accountable for polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) contamination, and federal funding for lead pipe removals — provide a foundation for the launch of our drinking water advocacy.

Our initial focus is building on existing grassroots efforts to ensure access to clean and affordable drinking water in Houston. Throughout successes, we learned that federal laws do not go far enough to address the lived reality of our communities, especially in confronting the environmental injustices we see across our watershed, or for the climate transition in front of us. Given the recent Supreme Court case, Sackett v. EPA, which has further eroded the Clean Water Act’s effectiveness in our region, we advocate for the protections that will keep our water clean and safe. In this section of our agenda you will also see specific goals to ease the burden on those members of our community.

Ensure all communities have access to safe, clean, and affordable drinking water by addressing contaminants and upgrading infrastructure

- The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) should develop a PFAS management plan that includes rapid hazard response, remediation, and protection of drinking water sources.

- Utilities within the City of Houston and Harris County should comply with EPA’s Lead and Copper Rule by replacing all lead service lines within 10 years.

- The City of Houston and Harris County should prioritize applications for federal water infrastructure funds through the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act (IIJA), including the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds (SRFs).

Increase access to affordable water for low-income communities

- Cancel existing non-commercial private water debt to alleviate financial burdens

- Develop an efficient water bill dispute system that:

- Establishes clear, fair procedures for contesting charges

- Offers multilingual support

- Streamlines issue resolution

Renew and increase funding for the Low Income Household Water Assistance Program (LIHWAP) to ensure continued support for families struggling with water bills.

Safeguard access to clean, potable water for low-income households

- Utilities within the City of Houston and Harris County should:

- Ban water shutoffs, except when deemed necessary during disaster events

- Waive late fees, reconnection fees, and suspend collection on overdue bills

- Leverage the One Water Community Cohort to:

- Facilitate meaningful dialogue between residents and city officials

- Ensure diverse stakeholder input in water policy planning and implementation

- Develop and implement an equity roadmap that addresses community needs

- Maintain public ownership and management of water systems

- Increase community engagement in water-related decisions

Improve water quality in our waterways

In order to achieve our bigger picture goal of ensuring that our city, state, and region strives for and reaches the highest standards of water quality, we propose these key interventions that will help ensure our waterways are clean and safe.

60 percent

of the city’s 2,500 miles of waterways are contaminated and unsafe for human consumption or exposure

Strengthen the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ)'s antidegradation review so it complies with the federal Clean Water Act

- Mandate that Texas Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (TPDES) permits include limitations to adhere to Texas Surface Water Quality Standards and have a robust anti-degradation policy.

- Require TCEQ to enforce a stringent process for permit applicants to demonstrate that public benefits of proposed development significantly outweigh potential environmental harm.

- Tighten regulations to eliminate broad interpretations of “necessary” discharges.

Enhance regional stormwater management through strengthened Municipal Separate Storm Sewer (MS4) permits

- The City of Houston, Harris County, and Harris County Flood Control District should improve their shared MS4 permit to:

- Implement more effective trash capture and removal systems with numeric trash reduction targets

- Incentivize the use of green infrastructure and low-impact development practices

- Enhance public and industrial education campaigns on proper waste disposal

- Strengthen construction site oversight for runoff control by increasing stormwater quality inspections and enforcement actions for non-compliance

- Secure Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) funding to support local implementation of MS4 permit requirements, avoiding unfunded mandates

Reduce Industrial risks

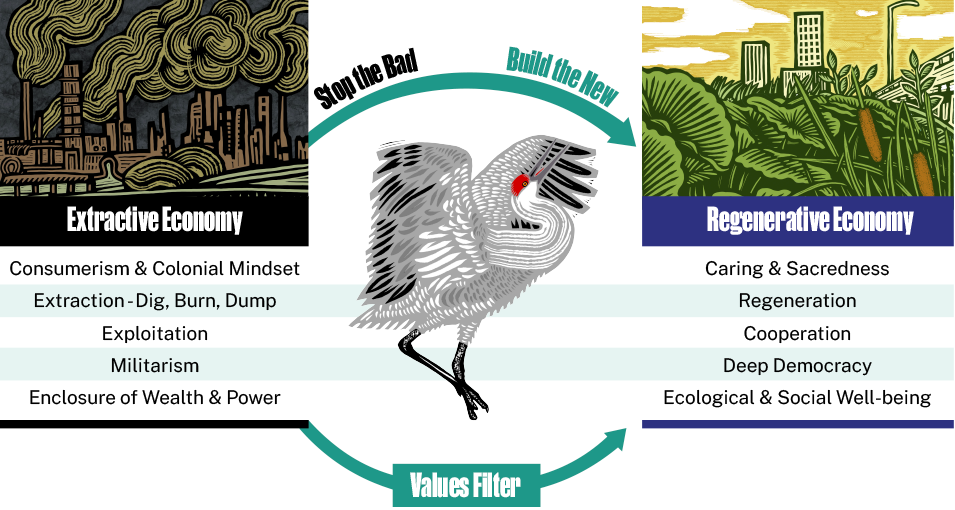

We follow the lead of Movement Generation and the Climate Justice Alliance in working toward a just transition. The two organizations worked together to articulate the Just Transition framework: a vision-led, unifying and place-based set of principles, processes, and practices that build economic and political power to shift from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy. The Just Transition framework recognizes the need to connect strategies to “stop the bad” with those that can “build the new” as well as bridge strategies to aid in this connection and transition.

With a Just Transition framework, we are working on ending extractive practices and the “dig, burn, dump” mentality, particularly by addressing industrial risks across our watershed. To build the new, we are focusing our work on two strategies named in the Just Transition framework: (1) working toward ecological and social well-being, especially by prioritizing the use of natural and nature-based infrastructure to address multi-faceted flood risks, and (2) deepening democracy, by bringing impacted community members to the center of decision-making processes. As bridge strategies, we are rooting ourselves in our own values, which resonate with the values of driving racial justice, social equity, and advancing ecological restoration in the Just Transition framework. As another bridge strategy, we are also working to change the rules and flow of funding streams towards communities left behind, especially at the local, state, and national levels.

Just Transitions Framework, adapted from Climate Justice Alliance

Stop the bad: Reject initiatives that accelerate climate change, damage communities and ecosystems, or weaken environmental safeguards

- Deny permits for onshore Gulflink and Sea Port (SPOT) oil terminals, along with other proposed projects that will increase fossil fuel dependency, pose spill risks to coastal ecosystems, and contribute to air and water pollution in nearby communities.

Stop the bad: The federal government should halt new offshore drilling to mitigate climate impact and protect coastal ecosystems:

- Withdraw leases awarded in the Gulf of Mexico through Lease Sales 259 and 261

- Reduce the number of offshore oil and gas lease sales currently planned for 2024-2029 from three to zero

- Implement mandatory preliminary hearings in communities where major engineering projects are proposed that could impact local ecosystems and residents

Bridge strategy: Reduce industrial risks by closing regulatory gaps and exclusions from environmental review

- Update EPA rules for plastics, petrochemical, and fertilizer facilities with stricter effluent guidelines and chemical safety standards

- Require full environmental review of Gulf offshore drilling by eliminating BOEM categorical exclusions

- Align TCEQ enforcement with EPA industrial standards and requiring facilities to meet Category 4-5 storm resilience standards

- Have the EPA Region 6 office encourage public access to critical disaster-planning information

- Have the Texas Legislature pass the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA) to ensure public disclosure of vital disaster-planning data

Build the new: Prioritize green and nature-based flood infrastructure in underinvested Black and Brown communities

- The City of Houston, Harris County, and Harris County Flood Control District should invest in nature-based flood mitigation systems by creating accessible green spaces along waterways that both serve as public recreation areas and showcase the value of our local biodiverse ecosystems.

Build the new: Prioritize nature-based solutions to address flooding and storm surge along the coast over a five-year timeline

- Fund priority ecosystem restoration projects from the Coastal Texas Study:

- Gulf Beach and Dune Restoration (Bolivar Peninsula/Galveston Island, Follets Island)

- Shoreline and Island Protection (Bolivar Peninsula, West Bay GIWW, Bastrop Bay, Oyster Lake)

- Suspend commitment to gray infrastructure in Coastal Texas Study pending comprehensive environmental review

- Support federal appropriations for municipal and county nature-based storm surge reduction through the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Hazard Mitigation Grants

- Prioritize oyster bed restoration and oyster-based structures for pollution filtration and surge protection.

Build the new: Center community members in decision-making processes relating to storm protections and industrial risks

- Reserve one Port Houston Commissioner seat for a resident of the Houston Ship Channel water justice zone

- Support and collaborate with the Harris County Community Flood Resilience Task Force (CFRTF) to advocate and prioritize nature-based solutions in flood-vulnerable areas and identified water justice zones

- Adjust county representation on the board of the Gulf Coast Protection District to proportionately match county populations

Protect Wetlands and Coastal Ecosystems

Our region is home to some of the most unique and diverse wetlands in the world. These wetlands are not only home to millions of migratory birds that benefit from the rich coastal habitat, but they also maintain water quality, serve as nature’s best defense against flooding, and capture carbon. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the lower 48 states have lost half of their wetlands since the 1780s. Section 404 of the Clean Water Act has been our main tool for protecting wetlands and has never gone far enough to protect large stretches of high-quality wetland ecosystems, under-protecting wetlands through a definition of “waters of the United States” which was not based in science and focusing on discrete developments and a flawed program for mitigation. In 2023, the Supreme Court further constrained the Clean Water Act’s effectiveness by requiring a continuous surface connection between wetlands and jurisdictional water bodies.

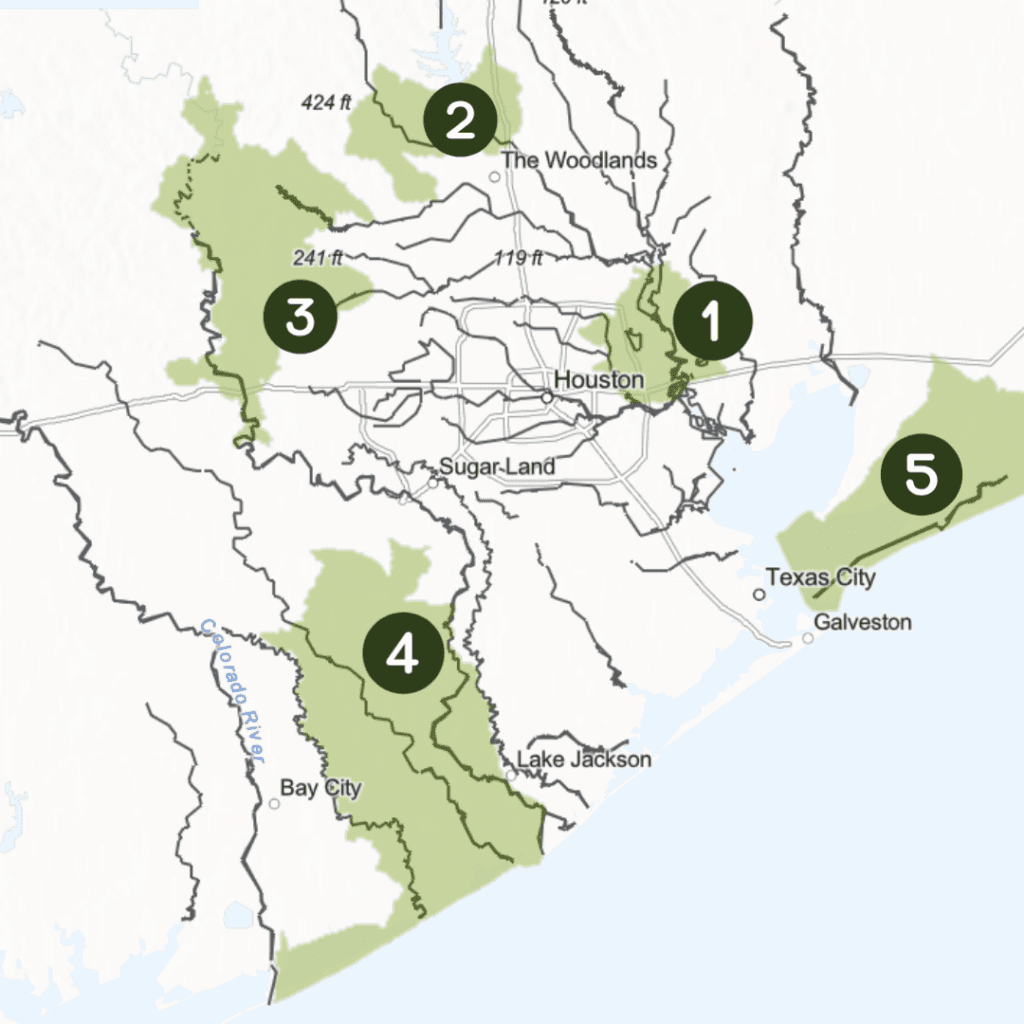

Through our work, we have identified five critical wetland areas, which contain large, undeveloped tracts of wetlands that can be conserved as part of a comprehensive flood and climate strategy. Our Wetland Watch and Wetland Walks programs connect community members to education and enforcement processes to spur policy change to protect wetlands. Additionally, our research collaboration with Stanford University aims to better understand the connection between upstream development and downstream flooding. This research will inform improved planning and agency decision-making to reduce flood risks in downstream areas.

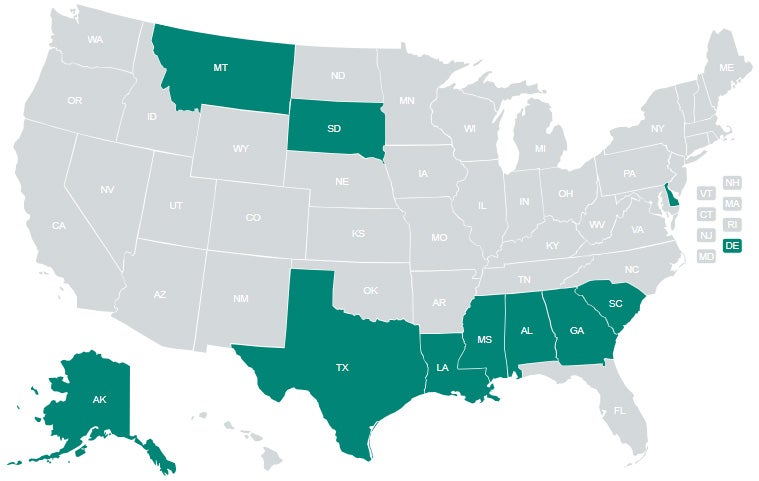

States with the

most wetlands and highest

proportion of wetlands to land,

but least protective laws

Source: Earthjustice

Strengthen the Clean Water Act's protections for wetlands

- Strengthen federal protections for wetlands to reverse the Sackett decision and reinstate the historic federal-state partnership that has protected our rivers, streams, and wetlands for over 50 years.

Protect and restore wetlands in the Lower Galveston Bay watershed

- Expand the San Bernard, Brazoria, and Anahuac National Wildlife Refuges (NWRs) to protect biodiversity hotspots and create larger buffers to industrial risks.

- Encourage U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to prioritize conservation of ecologically and culturally important areas through new or expanded NWRs.

- Center community leadership in wetlands protection:

- Ensure CBOs are integral to decision-making processes regarding wetland conservation and nature-based flood mitigation strategies

- Expand state parks and other natural public spaces to increase habitat connectivity and preserve wetlands, within and beyond the 100-year floodplains

- Coordinate wetland restoration across Harris County and surrounding counties to strengthen regional flood protection through inter-county partnerships.

- Create dedicated funding streams to advance restoration of degraded lands within 100-year floodplains, prioritizing communities disproportionately burdened by environmental hazards.

Remove barriers to local and regional wetlands protection at the state level

- Restore local control over wetlands and floodplain regulation by ceasing any further appeals of the HB2127 (the preemption law) and initiate steps for its repeal.

- Pass a green amendment to the Texas State Constitution recognizing a healthy environment as an inherent, indefeasible, generational legal right of all residents.

1. Lake Houston Flatwood Wetlands

2. Greater Lake Creek

3. Greater Katy Prairie-Pothole

Pimple-Mound Complexes

4. Trans-Brazos Region

5. Anahuac Coastal Marsh and Prairies

Our wetlands are the kidneys of the Texas Gulf Coast. They are critical to our flood protection and offer us all the chance to enjoy and connect with our unique natural surroundings.

To learn more and help protect our wetlands, see our 5 Critical Wetlands Story Map at bayoucitywaterkeeper.

org/5-critical-wetlands/ (embedded below)

Democracy

The kinds of interventions needed for just access to clean water and the conservation of Texas’ waterways are at odds with how politics has been designed to work in Texas. Notably, nearly two-thirds (65%) of Texas voters support government action to address climate change. Yet, our elected officials ignore these demands, leading us to support work that makes our democratic processes strong and accountable to the voters. After the 2023 legislative session, only 23% of Texans were confident that the legislature increased the reliability of the state’s electric grid, and only 22% of Texans were confident that the legislature improved the state’s water supply. This must change.

The ways democracy is degraded by political power-hoarding quite directly impacts our ability to be effective in our efforts to conserve our waterways and keep our water safe and clean. Nearly 65% of Texas voters support government action to address climate change, including more than 36% who strongly support it. In order to do so, we must work towards a more representative democracy that uplifts the voices of Texans most affected by water injustice.These reforms are necessary if we are going to create the kind of sustainable policy change that will ensure the other demands in our agenda will get fair consideration in our political system. Our work requires robust and trustworthy democratic systems, and while we will continue to keep water related policy issues at the center of that work, much of what we need cannot be achieved without the democracy reforms we name here.

Enhance the regulatory environment by increasing enforcement and oversight

- TCEQ should expand its resources to enforce environmental laws and pollution violations at the state and local level.

- Establish a state-level community enforcement program that empowers non-profit organizations and private individuals to:

- Monitor and report environmental violations

- Participate in enforcement decision-making processes

- Propose and advocate for remediation projects in affected communities

- Receive a portion of penalties collected to fund local environmental initiatives

- The TCEQ must provide regular audits and public reporting on enforcement activities, violation rates, and penalties collected.

Protect against (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) SLAPP suits

- Strengthen and maintain Texas’ anti-SLAPP statute to prevent corporate interests from weaponizing the legal system against environmental advocacy and community organizing.

Limit the amount of money Texas State candidates can accept from donors

The political influence of the petrochemical industry drowns out the voices of everyday Texans because of the large amounts of money the industry is donating to campaigns. Texas is one of only four states that does not limit political campaign contributions for state candidates.

Implement fair maps in Texas

Texas voters deserve district maps that serve to fairly represent them rather than divide their political power.

Enact online voter registration

Texans eligible to vote deserve to register with the ease and convenience currently available in the majority of states. Online voter registration has been successfully implemented already in 38 states.

Judicial Reform

- End lifetime appointments for Supreme Court Justices

- Mandate strong ethics rules for Supreme Court Justices to be subject to the same codified ethics rules that exist for all attorneys and all judges in the United States

- Require a supermajority of at least six justices to reach consensus before declaring a federal statute unconstitutional.

CONCLUSION

Bayou City Waterkeeper has grown in size and scope to include the way water shapes and is shaped by the ecosystems and communities in the region. While the federal Clean Water Act was the initial policy driver for watershed protection, our policy agenda leverages new opportunities and policy change strategies. We work in collaboration across disciplines and communities and intentionally create multiple points of entry to engage in our work. We see water as a connecting and clarifying force. We seek to form authentic connections in our watershed, and we understand that by addressing water injustices, we may confront and uproot the broader systems sowing injustice. We are bound by our organizational values – interconnectivity, fluidity, bold action, justice and equity, and regeneration. By approaching the issues in a comprehensive way, we can ensure that the solutions our communities are spearheading on the ground are locally sustainable and are accompanied by larger statewide efforts to make a systemic change towards one-water climate adaptation, water justice, just watershed investment, and rights of nature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Bayou City Waterkeeper is grateful to all who contributed to making this policy agenda possible. Special thanks to our leadership team—Ayanna Jolivet Mccloud, Usman Mahmood, Guadalupe Fernández, and Kristen Schlemmer—for guiding BCWK’s first-ever policy agenda, and to our dedicated staff, interns, and fellows for their valuable input throughout the process.

We thank our community partners—Elizabeth Love, Chloe Lieberknecht, Stefania Tomaskovic, Mary Anne Piacentini, Ben Hirsch, Dr. Robert Bullard, Dr. Denae King, Chrishelle Palay, Yasmín Zaerpoor, Alex Ortiz, Zoé Middleton, Danielle Goshen, Margaret Cook, Emily Warren, and Brittani Flowers—for their invaluable insights.

Our gratitude extends to the Center for Advancing Innovative Policy (CAIP) team for their facilitation, Artist Kill.Joy for their illustrations, Tecoltl for Spanish language translation, and Evan O’Neil for design.

Glossary

A

AMHI Average Median Household Income

B

BCWK Bayou City Waterkeeper

BMP Best Management Practices

BIL Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

BOEM Bureau Of Ocean Energy Management

BRIC Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities

C

Clean Water Act Enacted in 1972, a foundational environmental law in the US aimed at regulating the discharge of pollutants into the nation’s surface waters and ensuring the overall quality of these waters.

E

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

EPCRA Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act

F

FIF Flood Infrastructure Fund

FMA Flood Mitigation Assistance

H

HCFCD Harris County Flood Control District

HB2127 prohibits local governments from adopting ordinances, orders, or rules that go beyond what is already expressly authorized in state law

I

IIJA Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

J

Justice40 Initiative Under Executive Order 14008 the Federal government has made it a goal that 40 percent of the overall benefits of federal climate, clean energy, affordable and sustainable housing investments go to disadvantaged communities burdened by pollution.

L

LIHWAP Low Income Household Water Assistance Program

M

MS4 Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System

N

NWR National Wildlife Refuge

P

PFAS per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances

S

SEP Supplemental Environmental Project

SLAPP Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation

SPOT Sea Port Oil Terminal

SRF State Revolving Funds

SWIFT State Water Implementation Fund Texas

SWMPs Stormwater Management Practices

T

TCEQ Texas Commission on Environmental Quality

TMDLs Total Maximum Daily Limits

TPDES Texas Pollution Discharge Elimination System

TWDB Texas Water Development Board

U

USDA United States Department of Agriculture

USFWS United States Fish and Wildlife Service