Historically, Bayou City Waterkeeper has focused on grasstops advocacy, a top-down strategy that focuses on engaging decision-makers and those who have influence over public policy, primarily through legal strategies. In recent years, we have embraced grassroots advocacy, a bottom-up strategy that centers on lifting up the voices of local communities, people who are most affected by the policy, who in turn can reach out to decision-makers to communicate the change they want to see.

Considering the complexity of water challenges that our region faces — underinvestment in water infrastructure, underenforcement of industrial risks by oil and gas refineries, a lax attitude toward land and water-use regulation, historic red-lining practices, and unprecedented flooding and storm surges due to climate change — BCWK’s advocacy strategies have grown to embrace both a top-down and bottom-up approach. As we build community power through organizing, we take inspiration from local histories of rich cultural diversity and a history of environmental justice organizing.

What is community organizing?

Organizing is a form of advocacy. It is often campaign-based, centering on a problem or issue without resolution and then targeting an issue, institution, and or political figure with decision-making power to change policy or implement regulations to alleviate the problem.

According to the Midwest Academy Manual for Activists, community organizing is “a method for building power, particularly for underrepresented and marginalized groups who have traditionally been excluded from decision-making.”

Centering environmental justice

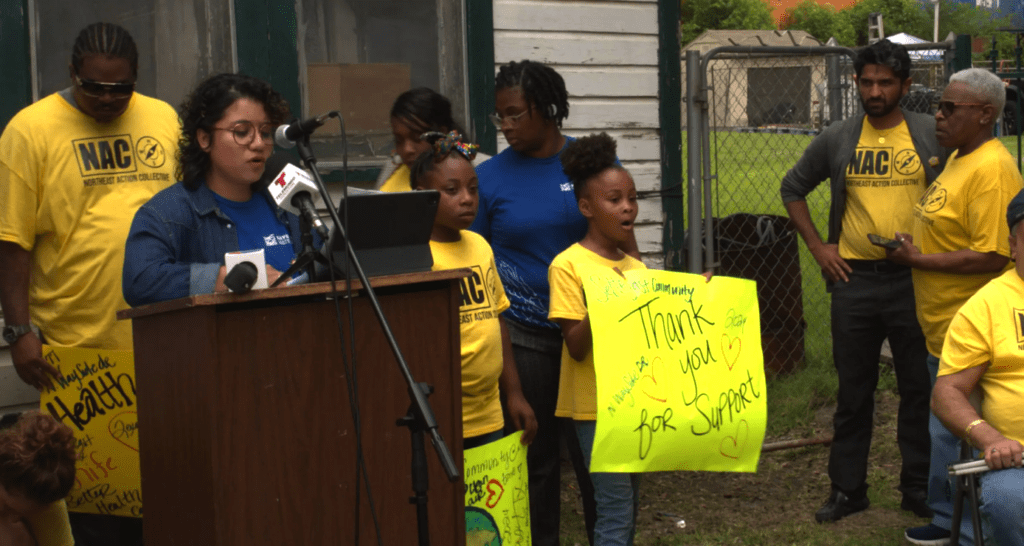

Justice is central to our organizing approach, which is an extension of local histories of environmental justice. We aim to center the histories of Houston and Gulf South grassroots environmental justice led by Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Asian, and immigrant communities, along with the leadership of women, gender non-binary individuals, and people with disabilities, all of whom are often on the frontlines of climate-related disasters. This intersectional environmental justice-based organizing approach addresses generational exposures to pollutants, lack of access to clean water, and insufficient green spaces. Like our predecessors, we aim to rectify the disproportionate environmental burdens faced by marginalized and underserved communities, to ensure that Houston’s communities, regardless of race, income, or other socio-economic factors, have equal protection from environmental hazards and equitable access to environmental benefits.

We seek justice for our people and also our ecosystems, and take inspiration from the Rights of Nature movement, a global movement to protect nature (rivers, mountains, and entire ecosystems and the life forms supported within them) as living entities by recognizing their legal rights. We see that our community and nature have rights and that organizing is a key tool to mobilize our communities to protect both. From an organizing perspective, this involves seeing the strength of our region’s ecosystems to mitigate flooding and water quality issues, while also restoring knowledge of water and honoring the labor of the people with a deep understanding of the local ecological landscape and lived experience.

Centering cultural strategy

Bayou City Waterkeeper has launched cultural strategy within our programs and organizing in the past year through 1) implementing language justice (translation and interpretation) and accessibility best practices into our community engagement strategies; 2) the launch of our inaugural artist-in-residence program; 3) by involving local communities in cultural planning processes advising the way we work alongside communities through our newly formed Community Research and Action Network (CRANe); 4) centering narrative change that calls out injustices while also centering asset-framing as a “cultural hack.”; and 5) prioritizing a unique form of education that builds power and action for under-resourced communities by unpacking barriers in understanding water policy through de-jargonizing and resource development.

By naming cultural strategy as part of our community engagement and organizing, we see this as a method to enhance diverse community participation and address traditional barriers for participation, spark creative thinking in water advocacy, and preserve and recall cultural heritage rooted in the wisdom of our regional waters.

According to Nayantara Sen, “When most people speak of culture, they mean dominant or mainstream culture. In order to transform political and social realities — and to ignite radical imaginative possibilities for our future — activists, artists, and movement leaders have been producing and intervening in culture for generations. By contrast, our definition of culture is decolonial. It centers the ways historically marginalized communities have maintained and transmitted their values. Our definition includes their traditions, belief systems, ways of living and knowing, and crucially, their ways of reclaiming, healing, and strengthening under conditions of cultural theft, suppression, and erasure…”

Community stands at the roots of our movements

As Bayou City Waterkeeper builds community power, leadership, and self-determination through our organizing and cultural strategy work, we take inspiration from the Clean Water Act, the main driver of our work. This federal legal framework for regulating discharges of pollutants into the waters of the United States started with community and public outcry due to the infamous 1969 Cuyahoga River fire in Cleveland, Ohio. The Waterkeeper movement, which Bayou City Waterkeeper is a member of, began in 1966 when a group of blue-collar fisherpeople on the Hudson River took a stand against illegal industrial pollution damaging the waterway and hurting their livelihood. The environmental justice movement, which led to federal executive orders in 1994 and in 2021, first gained traction in the 1980s in reaction to discriminatory environmental practices, including toxic dumping and municipal waste facility siting in predominantly African American and Latinx neighborhoods in Warren County, North Carolina and locally here in Houston.

As Bayou City Waterkeeper advocates for water policy solutions by leveraging legal strategies, and data-to-action frameworks, we are grounded in the fact that community is at the roots of all of our movements, and cultural strategy integration is essential in a region like ours with rich communities and ecosystems.

This blog post was written by Ayanna Jolivet Mccloud, Executive Director, in collaboration with Yudith Nieto, Bayou City Waterkeeper’s Organizing and Cultural Strategies Manager. Bayou City Waterkeeper protects the waters and people across the greater Houston region through bold legal action, community science, and creative, grassroots policy to further justice, health, and safety for our region.