This text was previously published in Cite: The Architecture and Design Review of Houston.

In September, the US Army Corps of Engineers released the Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Coastal Texas Study (CTS). The culmination of a five-year, $20 million study, the CTS encompasses a collection of technical assessments examining storm risks for the Texas coast. The stated goal of this process was “to determine the feasibility of constructing coastal storm risk management and ecosystem restoration features” to “reduce risks to public health and the economy, restore critical ecosystems, and advance coastal resiliency.” The CTS proposes a group of highly engineered projects spanning the full Texas coast, but efforts are concentrated around Galveston Bay and the forty-three miles of coastline on either side. If funded, these projects will cost $29 billion, create new local tax burdens of up to $100 million per year, and take twenty years to complete.

More than thirteen years ago, on the heels of Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Ike started a conversation about how to keep coastal and inland areas safe from storm surge. Nearly 100 people died, broken infrastructure infused floodwaters and soil with sewage and toxic pollution, and the city was disabled for weeks. Despite nearly a month of no power in some parts of Houston, the storm was considered a near-miss. At the eleventh hour, Ike changed its predicted course down the Houston Ship Channel and avoided a larger disaster on the scale of what local attorney Terence O’Rourke has called America’s own Chernobyl. This remains possible. Houston’s refineries alone account for 15% of national production and rely on thousands of tanks that are especially vulnerable to flooding and storm surge.

But in Houston, Ike cannot be our only reference point. Over the last decade, storms like Hurricane Harvey, Winter Storm Uri, and dozens of others have wrought serious damage. When considered alongside the growing acceptance of the reality of climate change, these disasters expanded the conversation Ike started into one of resilience. How can we live and thrive in a wet and increasingly precarious place?

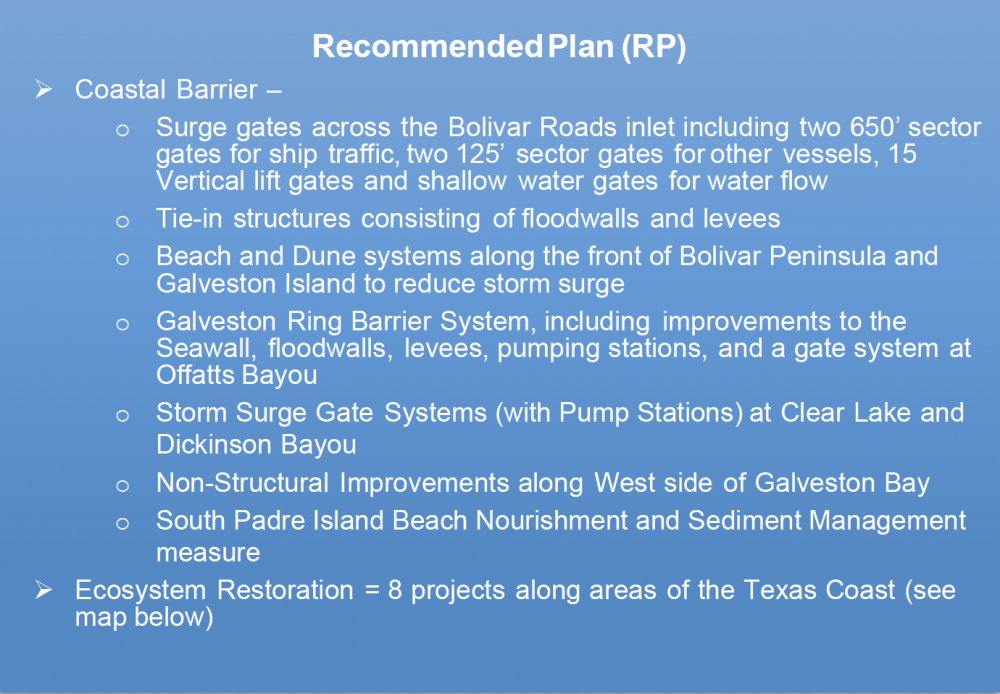

Despite its far-reaching potential to address the very real threats posed by climate change, the CTS narrowly focuses on the single danger identified by Ike: storm surge. To address storm surge in Galveston Bay, it champions a gated structure known as the Ike Dike. As proposed, a series of several gates will traverse two miles of open water, roughly tracking the path of the Galveston-Bolivar ferry across Galveston Bay. The largest of the gates will rise about two stories above the water when open and be anchored with sills on the seafloor, buttressed by three manmade islands, and connected to the shoreline on either side. Once complete, the gates can be closed when major storms approach, creating a buffer to incoming storm surges of up to twenty-two feet in height. For forty-three miles along Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula, the CTS also proposes construction of sand dunes rising twelve to fourteen feet from the shore. Around Galveston’s urban core, the CTS proposes a 23.5-mile “ring barrier” wall, twelve to fourteen feet tall.

The cost alone should not be a conversation stopper. $29 billion is an almost unfathomably large number, but compare this to the damage left by past hurricanes: Ike’s economic impact was estimated at nearly $30 billion, Harvey’s at $125 billion, and Uri’s at $195 billion. From a purely economic perspective, these disasters showcase a drastic need for ambitious responses. They warrant billions in investment. The value $29 billion could represent to communities who need protection now from flooding and other climate-related concerns is incalculable. There remains, too, the need to confront how investments in our resilience can be supported by the billion-dollar industries along the Ship Channel who stand to benefit from protections—and whose hazardous operations and contributions to climate change have created some of our largest risks.

How the CTS proposes to spend the $29 billion is the problem. By focusing on storm surge alone, the CTS’s view of what we need to protect is too narrow. The CTS’s proposed projects will not protect us from flooding from rainfall or high winds. These projects do not seriously account for sea-level rise or the increasing intensity of storms that we’ve come to anticipate when living on the frontlines of climate change in Houston. The version of the Ike Dike proposed won’t withstand storm surges associated with anything beyond a Category 3 hurricane—even though climate projections show we should expect that and more. And it’s a big red flag that the proposed barrier will take twenty years to build, while being designed for storms from the last century.

The CTS also leaves fundamental questions unresolved: it’s left unclear how the projects will affect communities bearing the largest share of flooding and pollution and alter the ecology and species of Galveston Bay. This means the CTS hasn’t addressed the full scope of threats to the most climate-vulnerable communities, even as it admits the construction of the Ike Dike will increase the toxic air pollution communities along the Ship Channel will have to endure on a daily basis. The CTS also delayed evaluating impacts to local ecosystems, including dolphins, turtles, and other marine species. By ignoring these concerns, the CTS declined to consider alternatives to the highly engineered structures that might offer more protections on a faster timeline. We won’t know if it will create new harms for the local communities and ecosystems it purports to protect until it is too late.

Resilience implies our urgent need to adopt new approaches to avoid past mistakes. Business can’t go on as usual. In Houston that means we cannot continue building in our floodplains and on our coasts. We must keep people out of harm’s way, and we must stop destroying natural flood protections and engineering partial fixes afterward. We must learn to work with, not against, nature. We cannot continue to leave behind the same communities with our investments or create new sacrifice zones. Equity must be a central, driving question.

Hurricanes, tropical storms, and other storms flood Houston throughout the year. They trigger cycles of disaster and recovery that overlay traditional seasons and unearth the large-scale problems that otherwise lurk invisibly around us: sewer overflows, leaking gas lines, benzene in the air, overdeveloped floodplains, filled wetlands, saturated drainage networks, loosely applied building regulations, and environmental laws made meaningless through under-enforcement. Threaded through all of this is a legacy of institutionalized racism that determines how we experience disaster, shaping who recovers from a storm and who is left waiting. It’s impossible to eliminate all risk, but each storm sparks anew the question of how we keep the most people safe in the decades ahead. These longer cycles of disaster, recovery, and inequity must inform our answers.

We need to do more now and in a coordinated way; we cannot leave people or ecosystems behind in the process. Early on, the CTS cast aside a promising vision for coastal resilience requested by environmental advocates, including Bayou City Waterkeeper: a non-structural, nature-based set of strategies that could be implemented on a faster timeline. This option contemplates moving the most vulnerable communities out of harm’s way; investing in upgrades to homes to withstand surges, floods, and high winds; protecting and restoring prairies, wetlands, and floodplains as a first line of defense; avoiding new development on the coast or within the 100-year floodplains; and aggressively strengthening and increasing compliance with building, floodplain, and other safety regulations, especially within the Ship Channel.

It isn’t too late to consider this as an alternative. Neither the $29 billion in federal and state funding, nor hundreds of millions in local taxes, have been approved. The project’s construction timeline gives us an uncomfortably long runway of time with which we can get started with smaller-scale solutions that could protect more people before the next major storm.

The CTS proposes solutions that don’t work to strengthen our natural systems or the communities hit hardest by disaster. Rather than getting lost in the details of engineering a silver bullet, a plan to protect our coast must embrace this place we call home in all its complexity. It must accept the reality of climate change and the transition that is before us. It must do the hard, creative work of imagining a better future for all of us who live on this stretch of the Texas coast.

Kristen Schlemmer is the Legal Director and Waterkeeper for Bayou City Waterkeeper, a Houston-based organization focusing on water quality and wetlands protection across our region with an emphasis on climate resilience and environmental justice.

Kristen Schlemmer is the Legal Director and Waterkeeper for Bayou City Waterkeeper, a Houston-based organization focusing on water quality and wetlands protection across our region with an emphasis on climate resilience and environmental justice.