Tropical storms and flooding are forecasted in Houston this Juneteenth, and some celebrations are being canceled and postponed. Yet, rain could provide a backdrop for reflections on the connections between water and this holiday and broader links to water justice and Blackness.

Water is a literal point of entry for Juneteenth. On June 19, 1865, more than 250,000 enslaved Black people in the state of Texas were set free by an executive decree when 2,000 Union soldiers entered Texas through the waters in Galveston Bay. Texas was the last, southernmost, and westernmost Confederate state to free enslaved African Americans.

In Houston, “the bayou city,” it is unsurprising that our origin story is anchored around water, often told at Allen’s Landing located at the confluence of Buffalo and White Oak Bayous, south of what is currently University of Houston Downtown. This site has been named the official birthplace of Houston because the Allen brothers purchased over 6,000 acres of coastal prairie and “settled” the city in 1836, just months after the Republic of Texas won its independence from Mexico. This version of Houston’s origin story often excludes Native people, migrants, and enslaved people. Yet, it was their labor and stewardship that built infrastructure on the complex, watery land of coastal prairies, marshes, wetlands, and swamps in this region. According to O.F. Allen, one of the Allen brother’s nephews, “The labor of clearing the great space was done by negro slaves and Mexicans, as no white man could have worked and endured the insect bites and malaria, snake bites, impure water, and other hardships. Many of the Blacks died before their work was done.”

We must acknowledge labor and loss, while also making space for multiple origin stories, especially around water. And in Houston, one of the most diverse cities in the U.S., we should center African Americans and people of color, and their histories around water, even while fraught.

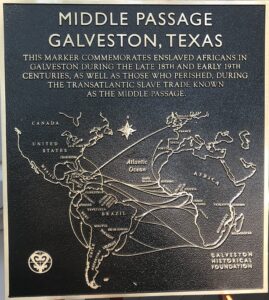

In Galveston, near the original Juneteenth site, is a historical marker on a wall at the Seaport Museum. This marker commemorates enslaved Africans who came to Galveston through the Middle Passage and those who perished. Of the 12 million enslaved people who were forcibly transported into the Atlantic slave trade from the West African coast between the 16th and 19th centuries, about 1.5 million died onboard ships, leaving about 10.5 million slaves to have arrived in the Americas. Middle Passage port markers, such as the one in Galveston, are part of Houston’s watery origin story and must be reclaimed.

It is through water and aquatic habitats in our region, that runaway enslaved people used their environment as sites of resistance, attempting to survive in the brush, from water in the creeks and bayous, and attempting to cross the Rio Grande, as part of the Underground Railroad to Mexico. Descendants of enslaved people in Mexico also celebrate Juneteenth due to these crossings.

Water recreation is also a critical component of water justice for African Americans with roots back to West Africa. Black people have rich histories within the water. Along the West coast of Africa, there is a long history of expert swimmers and fisher people. It is also the unexpected birthplace of wave riding and surfing. It was only in the context of slavery that waterways were transformed from sources of life, livelihood, and recreation to sites of danger and death for Black people, but we have to reclaim these rich cultural narratives of being in the water, alongside the injustices.

In Houston during segregation, African Americans visited Galveston’s Brown Beach and Sunset Camps, beaches officially designated for Black people. They also went to Emancipation Park, located in Houston’s Third Ward and the primary site of Juneteenth celebrations, starting in 1872, when it was purchased by four former enslaved African Americans led by Jack Yates. It is also the only park and swimming pool, built in 1938, that African Americans could use since Texas was still a segregated state. Most public pools in Texas were not legally desegregated until 1963 and remained a point of contention throughout the Civil Rights Movement, so this park held significant importance for African Americans throughout the city to connect and swim. While these were safe sites of water recreation for Black people, white-only pools and beaches were a battleground for the Civil Rights Movement. Swim-ins and wade-ins were key tactics for integration. Yet these protests by Black activists at white-only water sites sparked violent outbursts by white residents and law enforcement including nails placed at the bottom of pools, bleach and acid poured in pools, physical assault, and shootings.

Juneteenth is an opportunity to recall water justice histories among African Americans, the African diaspora, and in Houston, a water city; and to advocate for current water injustices that disproportionately impact African Americans in our city and nationally.

African Americans are more likely to be impacted by water injustices than any other group in the United States. This is evident in drinking water quality, as recent studies have revealed communities with higher proportions of Black and Hispanic/Latine residents are more likely to be exposed to PFAS, “a forever chemical” that is finally being regulated by the first-ever national, legally enforceable drinking water standard. Water pollution and quality issues are also evident in the fact that Black communities also have higher rates of raw sewage backups. In Houston, Bayou City Waterkeeper has analyzed and led litigation around sewage pollution that impacts Blacker and Browner communities and we continue to monitor this. Flooding also disproportionately impacts Black communities.

As we celebrate Juneteenth, it is an opportunity to see throughlines of water justice with Black identity and communities of color, and to also reclaim stories of water recreation and broader narrative change. These deep-rooted histories can inform advocacy as we continue to hold our decision-makers responsible for investing in our communities and advancing environmental justice.

Bayou City Waterkeeper protects the waters and people across the greater Houston region through bold legal action, community science, and creative, grassroots policy to further justice, health, and safety for our region.